In January I was fortunate to spend three days in Scottsdale, Arizona, with a small group of physicians. We had traveled from the US, Canada, and Norway to participate in the third annual educational meeting of Physicians and Ancestral Health (PAH). I didn’t mind that Scottsdale didn’t warm as promised, because our meetings – and even our “play” sessions – were so inspirational that I was happier working that taking a tourist hike or amble through old town.

PAH is a relatively new organization (with a still primitive website!), founded specifically as a forum where MD’s and DO’s can share our curiosity, insights, and experience regarding the study of ancestral health as it relates to the practice of medicine. There are various organizations with similar intentions, most notably the Ancestral Health Society, which includes all health care practitioners, and some online practitioner registries: Primal Docs and Paleo Physicians Network.

What does it mean to look at ancestral health practices, and why do it? Gathering information as best we can from the fields of anthropology (for civilizations existing long before us) as well as current physiology and medicine (for hunter-gatherer populations still existing), we can make a fairly good estimation of how people lived before the age of civilized life. When people find a way to feed themselves off the land, they will only stay alive if they are successful in figuring out what promotes good health. People living without the benefits of civilization certainly die more frequently at younger ages from infection or injury, it seems that once they survive their youth they have a chance equal to our own of surviving into their 70’s. Of greater interest is that their middle and later ages are largely untroubled by the chronic diseases that plague modern folks. So their average life span is less than ours (factor in all those early deaths which modern medicine prevents) but their “health span” is much greater than ours (factor in all those unhealthy aspects of modern civilization that are modern peoples’ downfall.)

We obviously don’t want to and can’t strip down to animal skins and walk out into the woods, but we can take observations of ancestral life, compare it with what we know of physiology as well as the findings of modern research, and make some pretty safe and sane recommendations for the average modern city dweller.

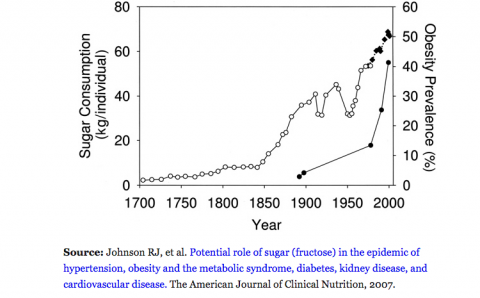

For instance, no civilization in recorded history has ever eaten as much sugar as we do now. We don’t have to go very far back to have at least a partial explanation of our expanding waistlines.

Now this graph is really interesting because the obesity prevalence FOLLOWS the increase in sugar consumption, and doesn't peak sharply until about 1980: what happened there? Our sugar consumption continued to increase, but the graph makes us question what else could be involved, as obesity rates increased much more rapidly. And that starts us down a long and winding road of investigation: do we really move a lot less than people did 100 years ago? What else has changed about how we eat, sleep, reproduce and socialize? Clearly there is not one simple factor, but many changes besides sugar consumption could be added to this graph, and the study of ancestral health gives us a framework for comparing the different factors of diet and lifestyle that might conceivably relate to understanding and reversing current disease trends.

A group of physicians, however, is not content to weigh different theories and bury our heads in research. Almost all the physicians at the meeting gave a presentation related to their work with patients. We heard about the components of a healthy diet styled on paleo principles, the meanings of different cholesterol measurements and their interrelationships, the value of meditation as well as that of chocolate, and the way to apply systems theory to modern disease. We all know that each disease in each individual is complex far beyond the conventional model of "name your diagnosis and I'll name your drug." We took a look at all the intersecting variables that can aggravate or ameliorate a case of multiple sclerosis, and discussed a systems approach to illness. I talked about the complexities of diagnosing and treating thyroid problems. I'll write up separate articles on what I think might be the most interesting to you.

We've had a continuing and lively exchange of information since the conference, and I expect that next year's conference will be at least double in size. Keep us in mind, I'm hoping the organization has a lot to offer the general public understanding of recovering and maintaining health!